If you’re fascinated with albinos, there is a single good book published on this topic. That is “Albino Animals” by Kelly Milner Halls.

Table of Contents

Albino animals

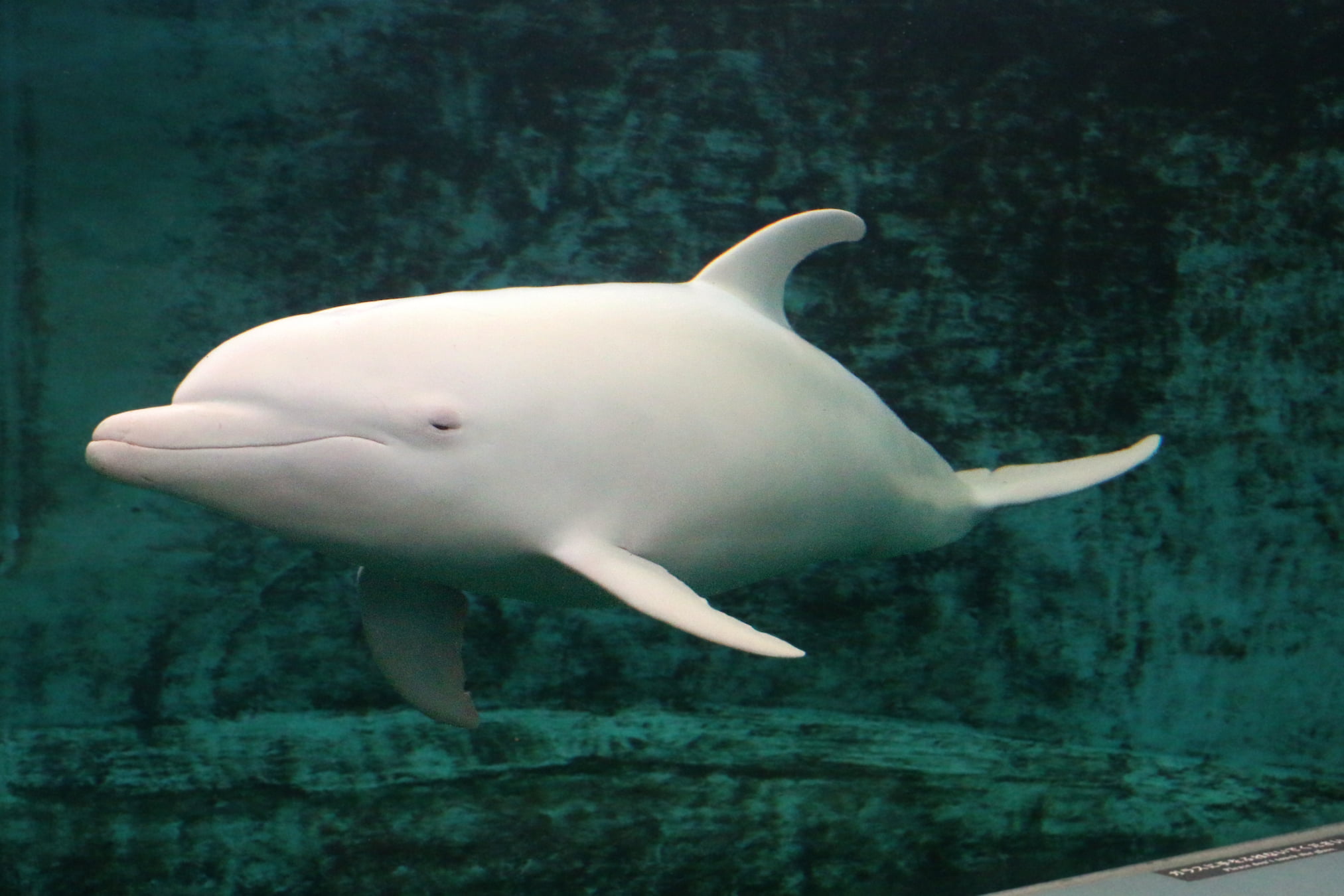

Tracing a backward course of existence far into the prehistoric eras of veiled mystery, albino mammals and birds perhaps always have existed in Nature’s marvelous web — astounding mutations with tenacious powers of singular repetition throughout the ages.

Sometimes there are outstanding individuals exquisitely breathtaking in their ghostly liveliness. Curious wild creatures that have been only partially touched by the wand that magically creates pure white when closely related family members wear conventional coats of brown and black — those exceptional challenges to man’s faculties for fundamental reasoning and enlightening explanation doubtless will be with us as long as the earth rotates in functional order.

But what is a true albino? By way of clarification, it should be pointed out that mammals and birds which wear dark fur in the summer and white coats in the winter are not albinos in an applicable biological sense. They are only enjoying a naturally-arranged color template set up purposely for the wellbeing of their bodies — protective coloration tied in closely with the machinating principles of environment and survival for both the hunted and the hunter. The eyes of the real color-change artists are normal. Springtime conversion to dark colors is usually complete in every detail. Albinos, on the other hand, wear coats that remain white forever, and their eyes never shed their pinkness.

In reality, the eyes aren’t pink. At least not in the sense that the outer coloring is pink. To say that the iris — the colorful part of the eye above the normal pupil — is transparent, or unpigmented, is perhaps the closest explanation of the presence of the pinkish hue. What most people don’t realize is that they are looking through the outer part of the albino’s eye, and into the retina which is richly supplied with blood. This exposure to blood, glimpsing through the clear iris, creates an illusion of surface pinkness of the eyes.

The eyes of every albino animal are very sensitive to light because too much light funds its way through the clear iris and into the retinal area. Consequently, the necessity for squinting to shut out some of the excess light is one of the characteristics marking the true creature in white. The pigmentation in normal eyes provides proper filtering to correct the amounts of light entering the eye for balanced utilization. Frequently the eyes of albinos become irritated by the torture of painful light, with blindness resulting in certain cases.

The word “albino,” derived from the Latin “albus,” meaning white, has possessed descriptive significance for multiple centuries in all parts of the globe. From the earliest times, albino animals have been regarded with esteem. Mad superstitions have sprung up around them. Hunters have been known to pass up albino deer, fearing they were ghosts of their ancestors. In India and Malaysia the white elephant — popular in slang expressions in these countries — is considered a sacred beast. Margaret Landon, in her true “Anna and the King of Siam,” said that “it was universally believed that a white elephant was none other than the reincarnation of some deceased king or hero… “

Albinism, occurring even in plants, fishes, and humans, is virtually without limitation in its world span. A yak in Tibet may be the only white specimen among thousands of dark-coated brethren. In Africa, a mother lion casts a quizzical eye at a white member of her family. In Colorado, a female crow is disturbed by the fact that the traditional black garb of her kindred has been cast off by one of her young, impudent, and ridiculous in the plumage of purest white. On and on, around the planet, in forests and in deserts, jungle, and plains, the birth, and growth of true albinos occurs on a scale determined by forces so complex that man is only partially able to understand their intricacies.

It is interesting to note here that while albinism is rare among many peoples, it is common among others. The Zuni and other Indian tribes of Arizona, for instance, have a rather high percentage of albinos among their members. Conversely, European races have about one albino for every ten thousand inhabitants. By the way of another bright contrast, the San Blase Indians of Darien have an albinism ratio that is seventy times greater than the average European. Explorers have found whole tribes of albinos in Africa, but some observers say our own Native Americans, as a whole, have consistently produced as many albinos as any race on earth, with the possible exception of cases where mankind has made a special effort to build up a pure albino strain.

All of which brings us to an interesting question.

Just how and why does albinism occur?

Naturalists in practically every progressive land on earth have applied themselves to the study of albinism. Many books have covered the subject —ponderous technical volumes with uncanny depths beaming scientific profundity. You can buy a book on albino topics, but it probably won’t be of any worthwhile value to you. It’s all about biochromes, genetics, ferments, color-bases, exposed eye capillaries, enzymes, chromogens, Mendelian recessives, etc. What you want is a fairly readable answer to the above question. Here it is, as simply as I can put it.

Albinos are all alike in that they are unpigmented. This lack begins to shape up in the maneuvers that go on in the development of the germ-cells — a process so intricate in the production of offspring that there are opportunities for dropping out certain items in the rules governing inheritance. Thus it may happen that some or all of the factors determining pigmentation may be lost in the shuffling and re-shuffling of the hereditary cards, and an albino is born, or perhaps a creature bearing only limited traces of albinism.

Actually, there is an arrest in the development of the pigment layers in the embryo, just as there may in some instances be an arrest in the growth of hair itself. Animals normally born with hair are in unusual cases born hairless. Chicks may hatch out and have white or pink legs instead of yellow ones. The uncompromising and oftentimes cruel quirks of mother nature almost relegate the albino to a comparative position of unimportance in the maze of physical inequalities that attach themselves literally to every form of life.

Carriers of the transmissible albinic factors need not be albinos or even part albino in the most minute visible degree. If the ingredients which make up the power to transmit normal tissues are entirely absent from the constitution of the individual, total or partial albinism in offspring can be counted on throughout the individual’s life span. Paradoxically, a true albino may not always carry the albinic factors, but his offspring, regular in appearance, may carry the taint through to succeeding generations so that in a third or fourth generation an albino may appear in full-bloom completeness. However, the mating of one true albino to another almost always results in albinic offspring — obviously because the odds weigh so heavily in favor of one or the other being a positive depository for the genes which cause the albinic mutation.

Summarizing the genetic aspect of albinism, the whole thing adds up to a fairly consistent course of hereditary deficiencies, with certain ratio rules that apply in breeding. However, these hold true only when the known background is introduced in experimental matings on a carefully planned and pre-observed basis. Otherwise, there is a disturbing loss of purpose in the study of structural coloration. In one test, an albino was back-crossed with a parent animal, and all offspring were exactly one-quarter albino. This rule doubtless would hold true in most instances.

In the world of birds, partial albinism occurs with rather startling regularity when a male bird having normal plumage is mated with an albino female. In the case of quail, one naturalist noted that all chicks resulting from such a mating were mottled, or part albino, but when the chicks reached adulthood, only a few retained any of their white feathers, and the eyes were not pink. It is, however, a safe wager to assert that nearly all of the chicks were carriers of the albinic genes, with the possibility of partial or full albinos cropping up in the offspring of most of the fifteen products of the cross-mating.

The females among both birds and mammals are said to almost invariably welcome the presence of any number of young ones touched by albinism. While the contrasting color may stand out like a sore thumb, the mother seems to understand the fact that the little creature belongs to her, and that they are not an alien bearing the stigma of having crept in from a puzzling outer world of other species.

It would be risky to say that there are certain mammals and birds which have never had an albino specimen in their ranks. It would, however, be safe to say that no albinos have ever been observed first-hand among a given species. We do know that the deer, seal, bison, squirrel, skunk, porcupine, muskrat, bear, fox, weasel, opossum, beaver, and many other mammals occasionally must tolerate the entry of a genuine albino into their clans. And among birds the ring-neck pheasant, meadowlark, robin, crow, blackbird, English sparrow, ruffed grouse, Cooper’s hawk, mourning dove, quail, red-tailed hawk, gold-finch, and a few others are among the most frequent types visited by the forces that inexorably mill the features of albinism.

Several years ago, I saw a white opossum in a timbered valley a few miles south of Indian Head, Pa. It was traveling at dusk along a small mountain stream and, while most albinos are supposed to have poor vision, this particular one apparently possessed pretty good eyesight and an unusually active gift of awareness.

A Canadian acquaintance once told me that he’d seen several albino porcupines and quite a number of the quilly fellows who bore only limited traces of contact with the magic albinic gift. He said that the true albino porcupines seemed rather timid and nearsighted, but this may have been merely the adherence to normal behavior patterns, for porcupines can appear quite dull and indifferent in a manner strictly peculiar to their species.

I also know a person from Colorado who recently trapped an albino otter and was offered a good amount of money from some wealthy individual for it. The trapper refused the offer, saying he wished to have the fur made up into a neckpiece for his wife. He chose a cheap fly-by-night concern and shipped his rare fur to them. After three weeks of waiting, he tried to contact the firm, but his calls weren’t returned. He was never able to locate the whereabouts of the phantom fur processors. His albino otter skin probably netted them a nice piece of money.

There is a common belief today that albino bison are vastly more common now that they were in the period when millions of these creatures roamed our continent. If this is true, and it probably is, on the basis of a proportionate number, of course, then the cause must lie in the fact that foundation herds chosen to rescue the animal from total extinction contained an above-average number of individuals able by their own albinic background to spread the genes responsible for albinism, either total or partial. Some observers say the total albinos in bison herds give unmistakable evidence of suffering eye discomfort and severely limited vision. Others, particularly hose a quarter to three-quarters albino, usually possess what appears to be normal eyesight and enough coloring of the iris to prevent squinting.

Mentioning the eyes of the albino once more makes me think of an albino deer places inside a wire enclosed in a New York State Park. The creature, wild, and terrified, plunged into the wire in repeated frantic attempts to escape. Observers soon were able to notice that the deer’s vision was extremely limited, and it could not see the wire netting until it was too late. Finally, the deer gave up and timidly sought cover in clumps of evergreens.

There is another facet in the lives of albinos that is worthy of mention here. That is the handicap of being hazardously conspicuous during all seasons except winter. Because of this, the best naturalists tell us the albino, in spite of their squinty vision, are gifted with a superb and unnatural power of instinct that warns of the closeness of danger. Albinos are admittedly the most difficult of all animals to approach in their wild state. They combine extra sensitive hearing with a better than average sense of smell and they end up surviving with cleverly geared habits that comprise a unique mixture of good judgment, awareness, caution, and alertness. Their startling whiteness is a source of betrayal in two ways: they see their albino enemies easier, but their enemies of all colors also see them easier. So nature, long ago, had to compensate a bit by endowing the albinos with a few functional physical blessings to offset some of the nasty inequalities fashioned buy the frequently faltering devices in the infinite creative setup.

Finishing thoughts

While reading this article, you have probably thought about white mice and rats. Are they always true albinos? Actually, they are not. They are bred to produce coats of white, but genetically they do not always turn out to be genuine albinos. Albino mice breed true to type almost always, but many white mice occur, which are not albinos, and this also is true of rabbits and other creature which man strives to develop through selective breeding so that a natural coat of white will be the unwavering rule.

I’ve already made a brief reference to the fact that albinos are found in most countries and climates. The fact that many of our four-footed wild-game are nocturnal in their feeding habits easily explains why albinos that possibly exist aren’t more often spotted.

If you’re fascinated with albinos, there is a single good book published on this topic. That is “Albino Animals” by Kelly Milner Halls.